Queen Cutlery & Servotronics Early Experiences with Collector Knives: the 1970s

Dan Lago, David Krauss, and Fred Fisher, 6-2-2023

Introduction.

This article focuses on how The Servotronics Corporation bought Queen Cutlery in 1969 and entered into a twenty-year evolution of changing the knives they made. Initially, they were company that manufactured knives as “tools” purchased at hardware and sporting goods they evolved into a company that relied on production of premier collectable knives.

Queen Cutlery grew out of Schatt and Morgan cutlery in 1922, and survived through the Great Depression with a small trade in skeleton knives for jewelry customers, and eventually, under the “Queen City Cutlery” name, developed a range of pocket and fixed blade knives for practical use. World War II and consistent Federal government contracts for military knives, greatly strengthened the company through the war years.

The best history of Queen Cutlery and their predecessor, Schatt and Morgan, is David Krauss’ (2002) detailed history of both company’s early years, as well as Queen’s success in re-establishing the Schatt & Morgan reproduction premium knives in 1991. He documents many of the fine knives made for collectors that came out of the factory after that time. This article adds details focusing on the 1970s beginnings of the transition. A future article will focus on the successful work in the 1980s, leading to the eventual return of the Schatt & Morgan brand.

Two decades to become a force in collector knives? Seems like a long time. The essential feature of this story can be summarized as a cautious, intermittent history of a small company, with complex corporate management, often on the brink of bankruptcy, learning to collaborate with other companies, and struggling to survive. The story has two components: the slow realization that that regular catalog cutlery that had carried the company over several decades was failing, and that converting to collector style knives was not easy, nor automatic. In short, this is a cutlery example of “You have to walk before you can run” in making knives collectors will want to buy.

Commemorative and limited-edition knives

Bernard Levine, in the 3rd edition of his Guide to Knives book notes that “limited edition” and “commemorative” knives are produced by knife makers primarily to induce knife buyers to buy more knives. Business is business. He notes that both limited edition and commemorative knives are usually sold at a higher price than a general run of the same knife, the knives do not necessarily represent more value to the collector and may not appreciate much in value. Cutlery companies release knives every year that commemorate something and pretty much anything can be fair game (including animals). He suggests always looking at the quality of the knife related to quality of normal production knives when considering a purchase. These are useful comments for a novice collector to consider.

In fact, “limited edition” is a fairly ambiguous term in the cutlery business. It may mean knives were in produced in a specific small quantity with specific handle material or blade/steel, but it also may be an advertising ploy where the word “limited” means limited to what the company can sell. “Limited” may also be used as a way to produce artificial scarcity, and greater profit for the maker. Limited editions can also be a company policy whereby they only make a fixed amount of knives each year, but make the same pattern each year. Finally, many knife clubs do have a finite number of yearly knives made for club members, clearly limited editions. There are lots of variations possible when discussing a “limited edition” knife and, a collector should consider the particular knife (and its appropriately well-made box) at every unique buying opportunity; and based on the above, buy what is appealing.

In the simplest terms “Commemorative” means that the knife pairs itself to some person of event, etc. Clearly the Queen’s first foray into such knives, the “Drake Well Barlow” is such a knife. It linked the knife with the town’s historical event of 1859 (over forty years before the Cutlery came to town). The commemorative knife creates and celebrates a relationship. And the same is true with the Queen Bicentennial Grand Daddy Barlow released in 1976. Queen’s first two commemoratives were well made knives and sported “extras”; special etches, tang stamps and/or serial numbers. The Grand Daddy Barlow came in a wooden display. More on these details later.

In addition to modern commemorative and limited edition knives, some knives can also be “rare” i.e. hard to find for a number of reasons. Historically some knives were made in large quantities but most were simply tools, used and thrown away when “used up.” Rare often means that a specific knife is out there, but it’s very hard to find or costly, as not many are known to exist in excellent condition. This is especially true for knives that are antique/historical knives; they are rare because so many of them were simply used up. However, there is a sub category of rare historical presentation knives, given on special occasions, often to people of note (and never used). Most of these knives have passed down in their original condition and are extremely rare (and costly).

Most people did not think about collecting pocket cutlery until the late 1960s. More recently, for American cutlery companies that cater to collectors, rare has come to mean produced only in (at times artificially) small numbers. This approach necessitates that companies continue to innovate and make knives that are novel enough that keep buyers coming back.

What makes a knife desirable to a collector? There are probably as many answers to that question as there are collectors. Pocketknives are generally well regarded if they are well-made, and have high levels of fit, finish and function; the “walk and talk” of traditional pocketknives. Increasingly, “desirable” has also come to mean “pretty”, knives that use more expensive or exotic handle materials and steels in aesthetic ways. Other reasons likely range from nostalgia to the satisfaction of simply holding a well-made tool in hand. For example, one of the authors of this article became interested in collecting when he saw an ad for a knife similar to the one his grandfather carried.

Queen Cutlery as a Maker of knives as tools

Certainly, Queen Cutlery and its predecessor Queen City Cutlery achieved their greatest stability and largest work force during World War II. They, like many American industries, were funded heavily to produce knives for military use – fighting knives, pruning knives, officers’ and enlisted men’s pocket knives, machetes. The most basic kind of “tools” that were valued only for how well they worked to achieve a critical job. Knives were needed in the millions – they had to be sturdy and able to take and keep a sharp edge. Nothing else mattered – they were expendable. The civilian market was somewhat similar. One used a knife until it wore out or was lost, was then thrown out and another was obtained. It is hard to imagine those roots leading to Schatt & Morgan collector knives that cost hundreds of dollars and would never expect to be used.

To provide a context for the larger shift in American Cutlery, it is useful to remember that the National Knife Collectors Association (NKCA) began in 1968 and was formally incorporated in 1972, when knife sellers got together to promote the selling of new, reproduction knives to the emerging collector market. (See NKCA in references)

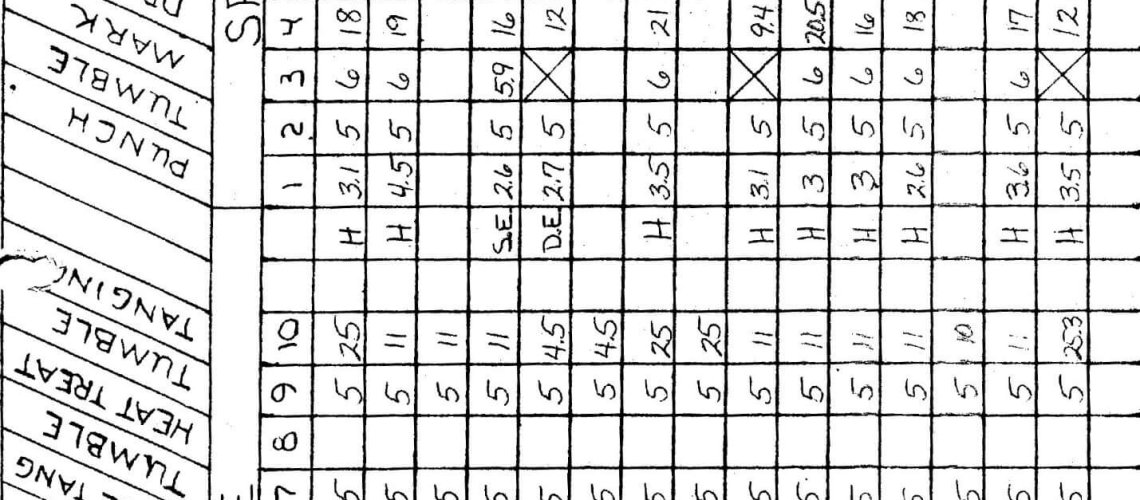

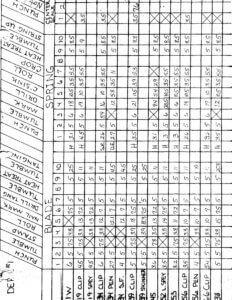

Figure 1. Queen Cutlery Innovation of Pocket knife models added to catalogs, 1947 – 1980. (based on “Guides” catalog knife # models, Queen cutleryguide.com)

With Queen City Cutlery patterns and cash from WWII military production, the newly organized company started strong, with 25 knives in their first catalog (1947, #82). They added many new patterns in the early and middle 1950s, but additional patterns slowed noticeably as that decade ended. Queen Cutlery produced larger lines of cutlery including tableware, scissors, axes, and increasing numbers of both pocket and fixed blade knives throughout the 1950s. They had developed a strong reputation for stainless steel knives that held an edge and represented good value for the money. They were essentially selling “tools.” Clarence Erickson died in 1961, and loss of his leadership can be noted in the years that followed (Figure 1). Walter Bell, a son-in-law of Clarence Erickson, assumed the Presidency of the company also in 1961. Harry Mathews, the last of the founders of the company, died in 1967 and his death probably “cleared the way” for the sale.

His sons, Robert Mathews and Gerald Mathews continued with the company, but they struggled with economic conditions that were hard for cutlery companies generally. In desperate bids to cut costs, Queen moved to delrin plastic handles and abandoned tang stamps in favor of less expensive blade etches. Queen’s tableware lines and kitchen knives faced dramatically increased costs and competition from the far east, and cultural changes placing less attention on formal dining. Queen’s management could not correct the downward slide and finally sold the company to Servotronics in 1969, although both brothers did retain positions in the company through 1975. As discussed in David Krauss’ American Pocketknives book, (the definitive history of Queen Cutlery), the decision to sell the company was made in 1961, but not completed until 1969 (Krauss, 2002, covers this time in pages 58-59).

Servotronics had a strong interest in recovering the costs of their acquisition of the company and pursued policies of selling parts for knives and immediately selling any completed knives, removing inventory from the company vault that had used to fill orders promptly. They did move to a single catalog for 1972 – through 1980 (Catalog 50), with annual price lists which had to show frequent cost increases. The 1970’s were a major inflationary decade. From 1973 – Arab Oil embargo inflations was at 8.8%, rising to a high of 14 % by 1980, due to a number of federal government macroeconomic policies (Refences: Investopedia.com). But Queen cutlery buyers had to experience much greater cost increases.

Two examples will show the trend in costs. In 1970, one dozen of #9 medium stockman knives and one dozen #19 premium trapper knives each sold to distributors for $41.40 (or $3.45 per knife). By 1978, the distributor price for the #9 medium stockman had risen to $6.85 (198.5% increase), and the #19 premium trapper had risen to $7.30 (211.5% increase), with no changes in the steel or handles. (The reference section has links the price lists on Queencutleryguide.com, “1970s price lists.”) The company needed to make a major change in the cutlery they were producing as their financial situation worsened.

Queen’s and Servotronic’s Response in the 1970s.

The details of how corporate decisions were made in the middle 1970s are not preserved in existing company records, (or perhaps those records have been lost), and most of the key people from that era are no longer alive. So, in a sense this article is a bit speculative, based on some facts, but not as thoroughly documented as a true historian would hope for.

Robert Stamp was a Servotronics employee who moved to Titusville in 1971, first serving first as “Materials Manager, “then as “Plant Manager,” then as “Vice President,” and finally, by 1981 as “President”. He progressively took charge of Queen Cutlery throughout the 1970s. He also had to answer to executives at the Ontario Knife Company in Franklinville, New York, (also Servotronics-owned) and for major decisions, directly to Servotronics management in Buffalo, NY.

Stamp’s management of the company had to be closely focused on making cautious decisions on expenditures and “modernizing” the company to cope with Emerging Occupational Safety and Health requirement (OSHA) he establishment of a committee with weekly meetings and reports. He also implemented a plan for both foremen and assistant foremen for most of the departments to attend a 30-minute meeting every morning to oversee the daily process as a way to increase management control of the details of making cutlery.

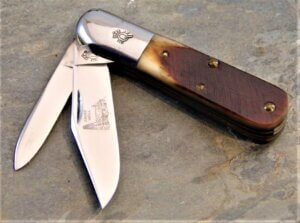

A first step on Queen’s path to collector knives is the development of the 1972 (50th company anniversary) that resulted in the company’s first collector knife, The Drake well commemorative Barlow. It is interesting to note that a local salesman, not the company President, came up with the idea and Robert Mathews (Then, Queen Vice President) promoted it successfully within the company and to collector book author Dewey Ferguson. (Reference section contains a link to the history of the 1972 Drake Well Barlow knife.) The knife is never mentioned in Robert Stamp’s correspondence from 1971- 2, although he did send several letters to Franklinville supervisors about special factory orders (SFO) for two Browning knives as they were in preparation. However, it is clear that Servotronics’ management eventually was persuaded to get involved and provided an exclusive contract for distribution of the Drake Well Barlow to a local Franklinville, NY company, Ischua Valley Outfitters.

Figure 2. The 1972 Drake Well Commemorative Barlow. Queen Cutlery’s first collector knife. Please see our story on this knife on our website: https://gbh929.a2cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Drake-Barlow-1972.-11-24-2020.pdf. (Internet photo.)

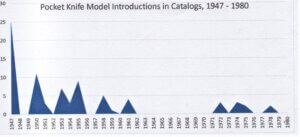

A second major example of Queen’s change in focus is shown in the company’s commitment to time and operations studies. Whether implemented by Bob Stamp, or Servotronics leadership, Stamp, as the leader of the Titusville cutlery factory, oversaw a huge commitment to “efficient time management” which described each operation in each department by time required for completion.

Figure 3, shows an example of the various operations and time required to complete each step required of every department in the factory. One can see only a few model numbers at the bottom of the page and the average time for each of the operations listed in the far left column for parts – in this case, “blades” and “springs”. We do not have record of how many times an operation would be “timed with a stop watch” before a summary page like this could be completed, or how many pages would be needed for all knife models at each department for every single “operation.” There were similar reports for every department. Totaling these reports provided the source of the eventual marketing claims about how many steps were required to complete a knife and an estimated cost based on worker payrolls.

At the time of the bankruptcy sale in 2018, the remaining records of these studies comprised approximately 81 cubic feet of storage space, many hundreds of 9″ x 12″ binders, each full of operation and time studies! They did not quantify how WELL a task was completed and were not viewed favorably by cutlers employed by the company, but they were certainly completed in large numbers for many years.

Workers felt the Servotronics management style added substantially to the “overhead” costs for the company. Bob Stamp was a likeable leader and treated men fairly. He prospered in the company, but he was not seen as an adventurous cutlery innovator.

In fact, Queen Cutlery under Servotronics also reinstituted tang stamps soon after taking over the company, beginning in 1971, after a decade of not stamping knives. Robert Mathews may have initiated this plan since he discusses it clearly in letters with Ferguson about the Drake Well Barlow knife in 1972. The company began trying out multiple stamps, producing many throughout the 1970s as a way of connecting with the growing collector market in their regular production catalog knives. Again, no mention of this in Bob Stamp’s letters for 1971-2.

Queen did offer some new patterns, such as the gamekeeper series, designed largely by Gerald Mathews, as competition to the highly successful Buck line of hunting knives. This series included quality stainless steel, micarta handles, serial numbers on the handle of each knife, high quality sheaths and much nicer packaging compared to earlier fixed blade knives. The Gamekeeper series initially had considerable advertising for the offering with package inserts and color pages in the 1972 catalog. As the company’s finances deteriorated, management gave little time for this series to establish itself. After introducing the Gamekeepers in 1972, certain knives began to be discontinued in 1976, and the rest of the line was eliminated by 1980 – 81. This was also the fate of a number of catalog knives such as the Mountain man 1446, which also left the offerings in 1981.

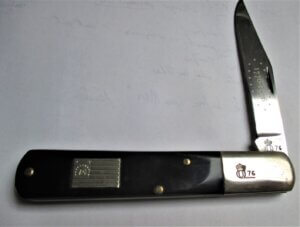

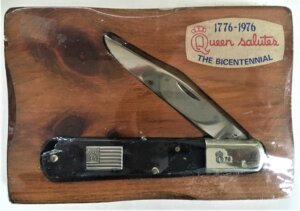

A significant “limited-edition” knife, the 1976 granddaddy bicentennial barlow (Figure 4, 5, and 6) was a high point in developing a capacity for collector knives in the mid-1970s.

Figure 4. Bicentennial Grand Daddy Barlow (#1450). The first Queen knife with a specially designed display case (the knife was enclosed in a cellophane wrap on a small Pine panel (Figure 5) with a label on the rear that also showed the serial number. The same serial number was shown on the pile side bolster, also a first for the company. Like the 1972 Drake Well Barlow, the tang stamp (which was offered for only one year) was repeated on the mark side bolster – large and easily seen – a winner for collectors. There was also a Revolutionary 13 star flag as the shield, and a star-studded etch on the blade – clearly a “dressed” knife.

Figure 5. Pile side bolster of the 1976 Bicentennial Granddaddy Barlow. The edition was claimed to be 15,000 knives (and the die for stamping those serial numbers would have allowed up to 99,999, a wildly optimistic number!). In fact, to date, we have not found any over 9,500 – still a large run for a limited edition knife.

Figure 6. Original cellophane packaging for the Bicentennial barlow. It must be admitted that the cellophane packaging did not seem permanent and it is extremely rare to find a knife in its original state, although some knives and pine panel have been “re-wrapped” so the connection between knife and display board can be confirmed. Most of these knives are usually seen separated from their display board. © David Krauss

This large barlow was the first Non-production knife with serial number for a collector market and it eventually led directly to the Rawhide large barlow (maybe with left-over blades) and many future Schatt & Morgan versions in the 21st century. So, supported by the enthusiasm of the bicentennial year, this knife was a significant step for Queen Cutlery, even though it is often not widely praised by current collectors, perhaps mostly due to the black delrin handle and display selected.

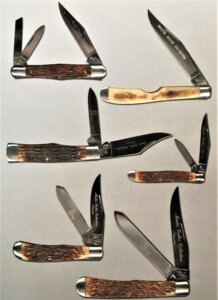

Figure 7. The Master Cutler Collection. © David Krauss

The Master Cutler Collection.

While the company faced serious financial concerns, they must have been aware that there was an increasing market in collector-oriented knives, especially with the Case Cutlery Company only a few miles away in Bradford, Pennsylvania. Remington, Shrade, and Camillus, limited edition knives were also being offered to the public in display boxes around this time. The Master Cutler Collection series of Queen knives were the first to use a custom packaging; first, hinged carboard boxes and then later “clamshell” boxes with inserts to hold the knife for display. They also were serialized. A Gunstock knife, set of two large and small trappers, whittler, peanut, and easy-open knife (last of the set in 1981) were part of this series and mostly, shared the same blade etch and production run (3000 pieces). So, this series was a first attempt to promote the continued purchase of knives over multiple years. The etch uses script on the main blade to identify “Master Cutler Collection” and “Stainless.” A master cutler is etched on a secondary blade holding a giant bowie knife. The easy open knife, with a thinner blade has a one-line capital sans serif etch, and is sometimes found with different bone handle patterns.

Queen has never provided information on sales of knives, but these must have done reasonably well as they were continued for several years. It is also apparent that they were done in a cautious way, using only regular production knives that previously had attracted customers, but with improved, traditional bone handle materials and only one a year (or two knives for the trappers). They also showed gradual improvement from carboard to clamshell display boxes over time (see Queen boxes 1971-1979). They did not take even half the amount of time to sell-out as the 1972 Drake Well Barlow. Even to this day, they are considered a “must-have” for collectors who are interested in the beginnings of Queen limited edition knives.

Against this modest success, Queen management had to realize their regular production catalog knives were not providing the expected revenue. Sales were dropping and costs were rising. At this time there is little documentation for this claim, but the dramatic changes in cutlery offered for sale by the end of the 1970s provides behavioral evidence. A cutlery company can offer to make whatever they want. But, customers will determine what they will buy and therefore what will stay in the catalog.

The Major Change in Products, 1978

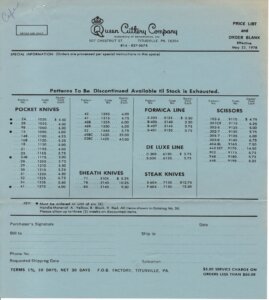

Figure 8. Price list of May, 22, 1978, showing Discontinued Queen Cutlery items.

In 1965, the company began making changes in their product line and eliminating slow-selling products. For example, they discontinued items in both Formica and Deluxe tableware. That policy gained strength as Servotronics purchased the company and the company management changed. It seems likely that such major changes are hard to imagine without major corporate decisions. For Servotronics that began in 1976, when a number of tableware items were dropped, and publicly with the 1978 “discontinued” announcement (Figure 8). By 1980 and finally in 1981, all tableware was discontinued and kitchen cutlery was greatly cut back. With gift sets as well as individual items, this reduction includes 100s of model numbers. (The Reference section includes links in Queencutleryguide.com for summaries of Series for “Deluxe line Tableware”, “Formica Tableware”, and “Kitchen knives by Model number.” Note the far right column, “YEAR” for when models were discontinued.)

And, as for pocketknives, 47 model numbers were discontinued, slightly over 25% of all the pocketknives offered. We can only guess that these knives were “slow-sellers” and were dropped to reduce costs of production. This re-focus allowed for concentration on higher selling knives to produce more revenue, even if it left customers a bit of reduced choice of patterns.

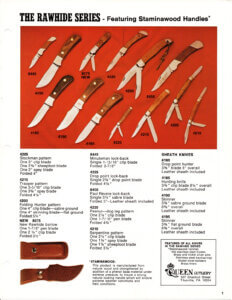

We know of no information on a 1979 price list or catalog, but beginning in 1979 and featured in the 1980 Catalog, the company also launched a major new line of knives, the Rawhide series. Rawhides looked very modern with stabilized brown wooden handles, large bolsters, blades sporting a large Rawhide blade etch with name, model number and 440 stainless steel. Each knife was individually packaged in a light brown one-piece box, a first for Queen Cutlery.

The large series included, in total, both fixed blade knives (7 models) and 13 folding knives including four lockblade versions. Two of the lockblades were given patriotic names (Figure 9) “Paul Revere” and “Minute Man.” Within a year these knives were upgraded as the Hawk Series, with each knife having a name, bird etches on the blade, and rarely seen double lockblades with higher level of polish and attractive black wood handles. This series was offered throughout the 1980s. Both these series seemed designed to provide more buyer choices and to compete with Buck Knives highly successful lockblade knives.

Figure 9. The large lockblade Rawhide knife, “the Paul Revere,” with Box. The Rawhide and Hawk Series both featured double locking blades – the only ones the company ever offered.

Figure 10. the introduction of the Rawhide Series in the color pages of 1980 catalog. The Rawhide series also had new knives added for a short time, including a swing guard, a toothpick, a canoe, and large barlow. They were considered by some collectors to be worthy of collecting being new and unusual to traditional Queen buyers. Some knives in this series sold very well. In particular, the larger premium hunting fixed blade patterns (4180, 4185, 4190) remained in the catalog with MANY handles changes through 2017 – for the rest of the company’s history). Overall, the Rawhide series was cataloged for 21 years ending in 2001

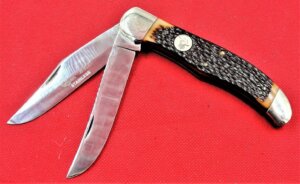

Queen also introduced another new series, Chipped Bark Delrin featuring a new style of Delrin plastic in a rougher finish (more like a traditional favorite Rodgers bone) with the company’s first shield on the mark side handle (Figure 11). The series included 13 pocket knives all previously strong-sellers in both the traditional Winterbottom bone, or later as Winterbottom Delrin. Chipped Bark series was blade etched as “Queen Stainless” including the a model number. They were positioned as a fancier knife, with the shield, and more attractive handle than plain brown wood “Rawhides”. Chipped Bark knives were first offered in 1982 and were again cataloged till 2001 – a long and successful run. They came individually packaged in a one-piece cardboard box. They ultimately replaced the former Winterbottom Delrin knives as inventories were used up.

Figure 11. A large two blade folding Hunting knife (#9145 in the Chipped Bark Series). Every knife in this set was exactly the same pattern as the remaining pocket knives knives from the earlier Winterbottom delrin line, but was provided with a new model number, so this knife “replaced” #39 in the 1982 catalog. (Internet photo.)

Except for some fixed blades and lock backs, very few of these knives required any new tooling. They were identical to the other pocketknife patterns they eventually replaced. Thus, began a policy the company used consistently for their remaining years: offering the same knife pattern in diverse handle materials. Any knife could be purchased in a less expensive wooden handle, a Delrin handle, or (on occasion) a fancier limited edition handle. Gradually, an entire handled “series” would be replaced by a new version with a different handle. For example, changing a handle material from Birds Eye Maple to American Walnut. Increased consumer choice was offered and a customer might be persuaded to buy more than one knife to add to their collection.

Queen had been a company committed to making the same products for many years, so there was a major Servotronics shift in the 1970s for innovation representing a severe challenge for management and workers. The company needed to have new materials available in correct amounts and be more flexible in repeatedly changing production set-ups as inventory and sales changed. Tableware machinery had to be removed or modified to change the focus to production of fixed blades or pocketknives. These kind of skills and perspectives would be essential for the future of the company, in modifying its own lines, and rapidly completing special factory orders (SFO), or as being nimble jobbers for other cutlery companies or private label knives.

Additionally, seeking new strategies, Queen also had to pay increased attention to other cutlery companies. The earlier comparision to products Buck Knives was making is clear. Queen tried to outdo Buck by adding details they thought would be pleasing to consumers in the “Gamekeeper Series.” At the same time, Queen learned from other companies like Case, Remington, Schrade, and Camillus to improve the boxes and packaging for their own knives, especially for collector-oriented limited-edition knives. It would take the rest of the next decade to build these skills into Queen, but the change clearly started in the middle and late 1970s.

While the decade began with field sales staff promoting limited edition knives, it ended with Queen’s top management accepting change and gradually moving to innovation and taking manageable risks in issuing collector knives.

The tension between Servotronics offsite management and the expert cutlers and sales staff in the Titusville factory must have been difficult throughout the 1970s. Robert (Bob) Stamp had a very difficult job as the President of Queen, but dependent on Servotronics management to approve his decisions. He should be given more credit than he has been, to date, for helping the company to survive a probable descent into bankruptcy and positioning Queen Cutlery to continue to grow. He and members of his sales force also must have cautiously convinced Servotronics to modify its conception of how that growth might proceed in the final years of the 1970s.

This story will be continued and gain strength in the 1980s, with three more articles covering 1980-1984, 1985-1987, and 1988-1998 .

This is a first generation article and if you have concerns or suggestions for improvement, do not hesitate to contact us. Thank you.

References.

How the Great Inflation of the 1970s Happened (investopedia.com)

Krauss, David (2002) American pocket knives: a History of Schatt & Morgan and Queen Cutlery. Krauss Publications. 3260 Euclid Heights Blvd, Cleveland Heights, OH. 44118.

Levine, Bernard (1993). Levine’s Guide to Knives and Their Values, 3rd Edition. DBI books, 4092 Commercial Avenue, Northbrook, IL. 60062.

(NKCA HISTORY OF THE KNIVES! – iKnife Collector.

Knife Talk: NKCA (National Knife Collectors Association) (knifetalkin.blogspot.com)

What does NKCA mean? – Hers and His Treasures

QueenCutleryGuide.com links:

Drake-Barlow-1972.-11-24-2020.pdf (myftpupload.com)

1970s-Price-Lists.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Queen-Cutlery-Boxes-1970-1979-5-23-2020.pdf (myftpupload.com)

Deluxe-line-tableware-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

formica-tableware-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Kitchen-knives-by-model-102019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Master-Cutler-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Chipped-Bark-Delrin-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Rawhide-10-2019.pdf (queencutleryguide.com)

Hawk-Rawhide-lockbacks-review-8-2019.pdf in Queencutleryguide.com)

QueenCutleryHistory.com Links: